Turning a traditional company into an internet-only operation isn’t hard. The hard bit is doing it while managing to still turn a profit.

And while many brands have struggled with the digital world, Auto Trader — one of my regular clients — has adapted impressively.

No more magazines

The company was once best-known for its weekly magazine full of ads for new and used cars. But the last edition rolled off the presses around a year ago.

The company was once best-known for its weekly magazine full of ads for new and used cars. But the last edition rolled off the presses around a year ago.

Today, the company relies on its website and mobile apps to reach car buyers, sellers and owners.

I can’t claim any credit for that long-term success, of course. But I am pleased that the first Auto Trader project I worked on recently picked up Digital Product of the Year at the British Media Awards.

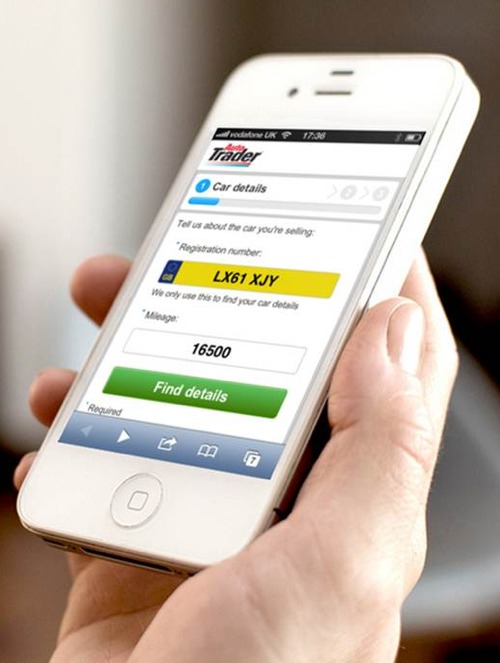

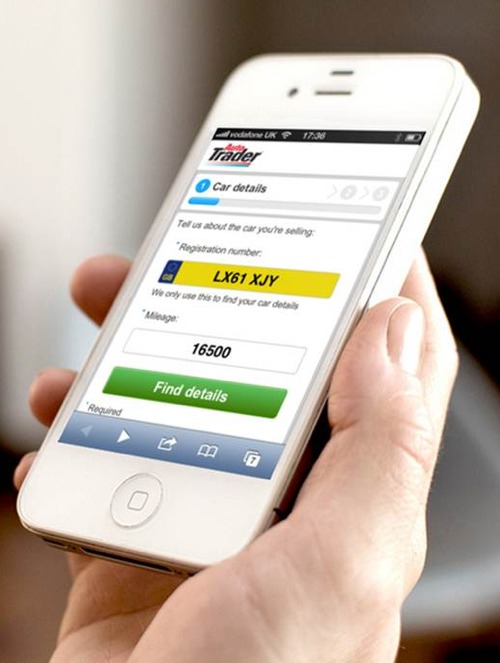

This substantial project was a complete rethink of the way people can advertise their cars through Auto Trader.

The vision was to create a process that would function across desktop and mobile devices, allowing users to switch to the most convenient device at any point.

For instance, if you need to take photos of your car, you can just grab your smart phone and upload them from there.

Simplifying a complex process

Creating an ad for your car is a complex process. You have to enter detailed information, upload images and constantly think about how to show your car in the best light.

I came into the project relatively late on, so most of the credit for the experience should go to the team that worked on it from the start.

However, I did craft virtually all the content in the process, from form labels and error messages to hint and help text. This consistent, friendly copy is designed to help and encourage visitors through the process.

Although very similar, the desktop and mobile experiences are tailored to take advantage of each device’s capabilities. This introduced the challenge of delivering subtly different content while maintaining a consistent, logical experience.

It took a while for everything to come together, but I think the result is a great example of the power of UX content and microcopy.

How did it turn out? You can see for yourself by creating an ad on Auto Trader. But as far as the British Media Awards go, it’s a winner.

Read my case study to learn more about this project.

In The Economist, nothing ever spreads like wildfire

It’s often said that good writers should read often and read widely. One source of consistently strong writing is The Economist.

Although you can find superb prose on its website, the magazine is well worth its £5 cover price.

At face value, you might expect it to be a dry, sober read. But The Economist brings complex subjects to life through writing that’s exceptionally clear and instantly engaging. Here are a couple of examples.

Using unnecessary words

Published recently, this moving piece examines how Northern Ireland is dealing with crimes committed during the troubles.

It includes an interview with June McMullen, whose husband was shot in 1981.

The first quote in the piece ends with three words that hint at the human cost of political wrangling and help the reader paint a picture of the interview in their mind (the emphasis is mine):

‘“I knew he couldn’t have survived it,” she recalls, over tea in her spotless kitchen. “Johnny was pronounced dead at the scene, so he was.”’

That ‘so he was’ is a typically Northern Irish turn of phrase. Including it in the piece seems to contradict a key rule of The Economist Style Guide (‘if it is possible to cut out a word, always cut it out’). Yet it adds detail and introduces some emotion, drawing you into the piece and enticing you to read further.

Knowing when to break the rules is, it seems, an important part of crafting articles fit for The Economist.

Putting a new twist on an old cliché

In the same edition, there’s a fascinating article about how new crop strains could help pull millions of people out of poverty.

The style guide’s first rule is ‘never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.’ The opening paragraph of this piece is notable for following it:

‘Borlaug’s varieties put out more, heavier seeds instead. They caught on like smartphones.’

In The Economist, good ideas don’t spread like wildfire, sell like hotcakes or grow like weeds.

They do something more original, because clichés should be avoided like the plague. Ahem.

For more writing inspiration, check out The Economist Style Guide and website.

Image: Flickr user woodleywonderworks under a Creative Commons licence.

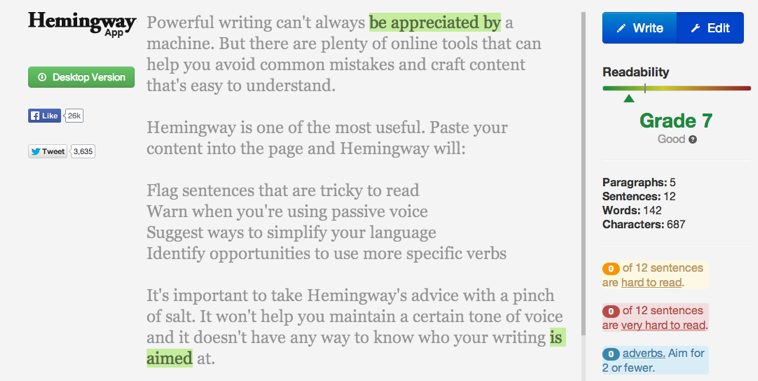

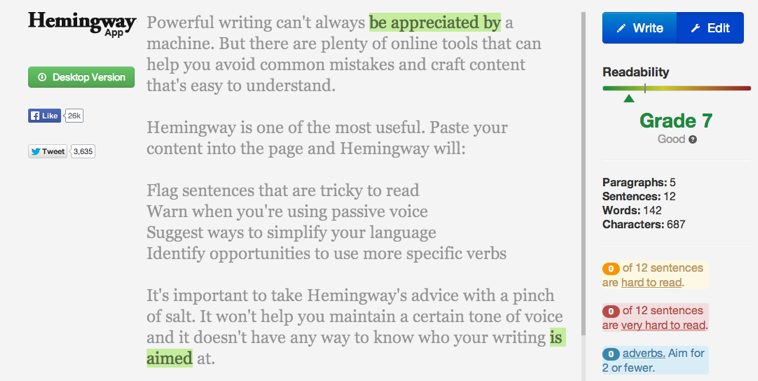

Powerful writing can’t always be appreciated by a machine. But there are plenty of online tools that can help you avoid common mistakes and craft content that’s easy to understand.

Hemingway is one of the most useful. Paste your content into the page and Hemingway will:

- Flag sentences that are tricky to read

- Warn when you’re using passive voice

- Suggest ways to simplify your language

- Identify opportunities to use more specific verbs

It’s important to take Hemingway’s advice with a pinch of salt. It won’t help you maintain a certain tone of voice and it doesn’t have any way to know who your writing is aimed at.

However, it’s one of the most effective ways I’ve found to sanity check articles, blogs posts and other content. File it alongside spelling and grammar checkers as another useful tool to tighten up your writing.

The company was once best-known for its weekly magazine full of ads for new and used cars. But the last edition rolled off the presses around a year ago.

The company was once best-known for its weekly magazine full of ads for new and used cars. But the last edition rolled off the presses around a year ago.